Predicting Car Prices using KNN

Predicting Car Prices

The goal of this project is to practice machine learning workflow by predicting car prices using dataset containing car characteristics. The dataset comes from the UCI’s machine learning repository.

Disclaimer: This project is part of the guided project for a Data Scientist Path on dataquest.io.

Introduction

Let’s first read the dataset and explore it to get a better understanding of it. Since the original dataset doesn’t have column headers in it, we need to provide the list manually.

The numeric feature columns in the dataset are:

- normalized-losses

- wheel-base

- length

- width

- height

- curb-weight

- engine-type

- num-of-cylinders

- engine-size

- bore

- stroke

- compression-rate

- horsepower

- peak-rpm

- city-mpg

- highway-mpg

The target column is price.

# import necessary libraries

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import collections

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

%matplotlib inline

from sklearn.neighbors import KNeighborsRegressor

from sklearn.metrics import mean_squared_error

# enable pandas to show all columns

pd.options.display.max_columns = 99

# list of columns names

columns = ['symboling', 'normalized-losses', 'make', 'fuel-type', 'aspiration',

'num-of-doors', 'body-style', 'drive-wheels', 'engine-location', 'wheel-base',

'length', 'width', 'height', 'curb-weight', 'engine-type', 'num-of-cylinders',

'engine-size', 'fuel-system', 'bore', 'stroke', 'compression-rate', 'horsepower',

'peak-rpm', 'city-mpg', 'highway-mpg', 'price']

# read the dataset

cars = pd.read_csv("imports-85.data", names=columns)

# check first few values

cars.head()

| symboling | normalized-losses | make | fuel-type | aspiration | num-of-doors | body-style | drive-wheels | engine-location | wheel-base | length | width | height | curb-weight | engine-type | num-of-cylinders | engine-size | fuel-system | bore | stroke | compression-rate | horsepower | peak-rpm | city-mpg | highway-mpg | price | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3 | ? | alfa-romero | gas | std | two | convertible | rwd | front | 88.6 | 168.8 | 64.1 | 48.8 | 2548 | dohc | four | 130 | mpfi | 3.47 | 2.68 | 9.0 | 111 | 5000 | 21 | 27 | 13495 |

| 1 | 3 | ? | alfa-romero | gas | std | two | convertible | rwd | front | 88.6 | 168.8 | 64.1 | 48.8 | 2548 | dohc | four | 130 | mpfi | 3.47 | 2.68 | 9.0 | 111 | 5000 | 21 | 27 | 16500 |

| 2 | 1 | ? | alfa-romero | gas | std | two | hatchback | rwd | front | 94.5 | 171.2 | 65.5 | 52.4 | 2823 | ohcv | six | 152 | mpfi | 2.68 | 3.47 | 9.0 | 154 | 5000 | 19 | 26 | 16500 |

| 3 | 2 | 164 | audi | gas | std | four | sedan | fwd | front | 99.8 | 176.6 | 66.2 | 54.3 | 2337 | ohc | four | 109 | mpfi | 3.19 | 3.40 | 10.0 | 102 | 5500 | 24 | 30 | 13950 |

| 4 | 2 | 164 | audi | gas | std | four | sedan | 4wd | front | 99.4 | 176.6 | 66.4 | 54.3 | 2824 | ohc | five | 136 | mpfi | 3.19 | 3.40 | 8.0 | 115 | 5500 | 18 | 22 | 17450 |

# check columns and observations

cars.shape

(205, 26)

Data Cleaning

Machine Learning algorithms can’t treat missing values on their own. For that reason we need to treat missing values. From the output above we immediately can see that normalized-losses column contains missing values in the form of “?”. We need to first replace “?” values with numpy.nan across the dataset. This will help us to easier convert other columns to required datatypes.

# replace ? values with np.nan

cars = cars.replace("?", np.nan)

# check datatypes

cars.dtypes

symboling int64

normalized-losses object

make object

fuel-type object

aspiration object

num-of-doors object

body-style object

drive-wheels object

engine-location object

wheel-base float64

length float64

width float64

height float64

curb-weight int64

engine-type object

num-of-cylinders object

engine-size int64

fuel-system object

bore object

stroke object

compression-rate float64

horsepower object

peak-rpm object

city-mpg int64

highway-mpg int64

price object

dtype: object

Now that we have replaced the “?” values, let’s convert columns containing int or float values to their correct data type

# list of columns to convert

cols = ["normalized-losses","bore","stroke","horsepower","peak-rpm","price"]

# convert the values to their appropriate datatype

for col in cols:

cars[col] = pd.to_numeric(cars[col], errors='coerce')

Rerun the datatypes cell to check if the conversion was successful.

Now let’s look at the columns which have these missing values and decide on how to handle them.

# Check for missing values

cars.isnull().sum()

symboling 0

normalized-losses 41

make 0

fuel-type 0

aspiration 0

num-of-doors 2

body-style 0

drive-wheels 0

engine-location 0

wheel-base 0

length 0

width 0

height 0

curb-weight 0

engine-type 0

num-of-cylinders 0

engine-size 0

fuel-system 0

bore 4

stroke 4

compression-rate 0

horsepower 2

peak-rpm 2

city-mpg 0

highway-mpg 0

price 4

dtype: int64

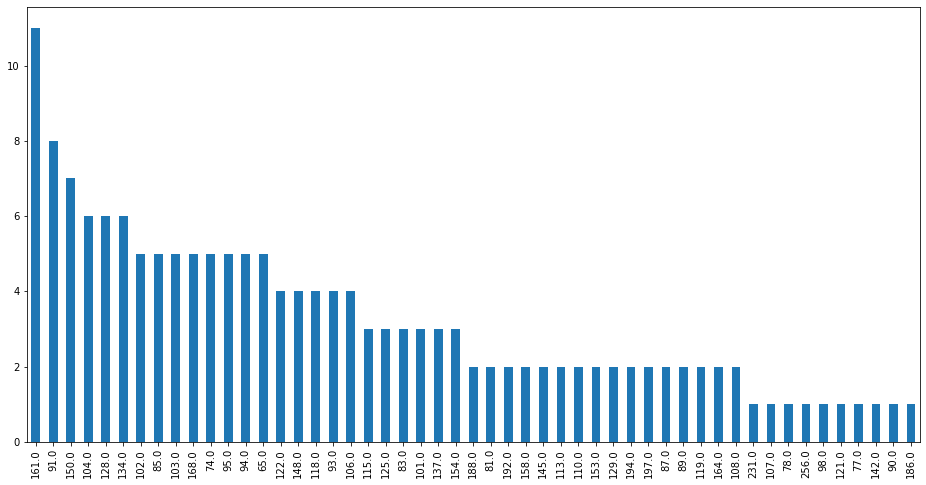

We can see that there are 41 null values out of 205 total records in normalized-losses. The missing values are 25% of all records. To handle this column entirely we can fill the missing values with the average value or drop the column entirely. We won’t remove the missing rows since this is a big part of the dataset. To decide on this, let’s check the distribution of values in the normalized-losses.

cars['normalized-losses'].value_counts().plot(kind='bar', figsize=(16,8))

<matplotlib.axes._subplots.AxesSubplot at 0x1c3597dd898>

We can see that the distribution for this column is right skewed. Thus we won’t be imputing using average since this might skew our results and introduce bias into this column. One potential solution would be to use mean imputation after normalizing the column, which we will do.

# normalize the column

cars['normalized-losses'] = (cars['normalized-losses'] - cars['normalized-losses'].mean()) / cars['normalized-losses'].std()

# impute with average value

cars['normalized-losses'].fillna(cars['normalized-losses'].mean(), inplace=True)

Rerun, the cell showing missing values to ensure that the imputation was successful. We can also observe that there are few missing values for columns such as price, horsepower, peak-rpm, bore and stroke. We will also normalize them and impute with average value.

# columns to be treated as per above

cols = ['bore', 'stroke', 'peak-rpm', 'horsepower', 'price']

# normalize and fill missing values

for col in cols:

cars[col] = (cars[col] - cars[col].mean()) / cars[col].std()

cars[col].fillna(cars[col].mean(), inplace=True)

Rerun the cell generating null value count and make sure they are treated.

Univariate Model

Now let’s start with a univariate k-nearest neighbors model as part of our project for predicting car prices. Starting with simple models before moving to more complex models helps us structure your code workflow and understand the features better.

To enhance and simplify our model testing workflow, we will create a function that encapsulates the training and simple validation process.

# function to knn_model training and validation

def knn_train_test(train_name, target_name, data):

# make a copy of the dataset

df = data.copy()

# number of observations for split

obs = int(df.shape[0] / 2)

# split the data into train and test

train_df = df.iloc[:obs]

test_df = df.iloc[obs:]

# reshape the values since we have a single feature

train_data = train_df[train_name].values.reshape(-1, 1)

test_data = test_df[train_name].values.reshape(-1, 1)

# instantiate and fit the model

knn = KNeighborsRegressor()

knn.fit(train_data, train_df[target_name])

# make predictions and evaluate

preds = knn.predict(test_data)

rmse = mean_squared_error(test_df[target_name], preds) ** (1/2)

return rmse

# use the function to train a model on normalized-losses

knn_train_test('normalized-losses', 'price', cars)

1.0768788918340664

Resulting rmse is based on the model that uses only one feature normalized-losses. We can test additional features to see how our model performs.

# use numeric features

numeric_features = ['wheel-base', 'length', 'width', 'height',

'curb-weight', 'engine-size', 'compression-rate',

'city-mpg', 'highway-mpg', 'horsepower', 'peak-rpm']

# loop through models with individual feature

for col in numeric_features:

result = knn_train_test(col, 'price', cars)

print("RMSE for model with {}: {}".format(col, result))

RMSE for model with wheel-base: 1.214252890227465

RMSE for model with length: 1.1107969135114395

RMSE for model with width: 0.8581184488064216

RMSE for model with height: 1.3712276576274274

RMSE for model with curb-weight: 0.7526797743700095

RMSE for model with engine-size: 0.6066522674323407

RMSE for model with compression-rate: 0.9980929742948769

RMSE for model with city-mpg: 0.6071818370617673

RMSE for model with highway-mpg: 0.5904065996733864

RMSE for model with horsepower: 0.6212450466337898

RMSE for model with peak-rpm: 1.1696138374863996

While the models above are not indicative of performance, but it seems that model with city-mpg feature has the lowest error on the model.

Next, let’s modify our function to accept a k parameter and rerun our univariate model with the above features to see the performance. We will use k values of 1, 3, 5, 7 and 9 to see which model performs well.

# function to knn_model training and validation - modified

def knn_train_test(train_name, target_name, data, k=5):

# make a copy of the dataset

df = data.copy()

# number of observations for split

obs = int(df.shape[0] / 2)

# split the data into train and test

train_df = df.iloc[:obs]

test_df = df.iloc[obs:]

# reshape the values since we have a single feature

train_data = train_df[train_name].values.reshape(-1, 1)

test_data = test_df[train_name].values.reshape(-1, 1)

# instantiate and fit the model

knn = KNeighborsRegressor(n_neighbors=k)

knn.fit(train_data, train_df[target_name])

# make predictions and evaluate

preds = knn.predict(test_data)

rmse = mean_squared_error(test_df[target_name], preds) ** (1/2)

return rmse

# use numeric features

numeric_features = ['wheel-base', 'length', 'width', 'height',

'curb-weight', 'engine-size', 'compression-rate',

'city-mpg', 'highway-mpg', 'horsepower', 'peak-rpm']

# dictionary to store model results

lowest_rmse = {}

# loop through models with individual feature

for col in numeric_features:

for k in [1,3,5,7,9]:

result = knn_train_test(col, 'price', cars, k=k)

lowest_rmse[(col, k)] = result

lowest_rmse

{('wheel-base', 1): 1.0200915246848115,

('wheel-base', 3): 1.1330559244770682,

('wheel-base', 5): 1.214252890227465,

('wheel-base', 7): 1.1050644625745172,

('wheel-base', 9): 1.0706582345927034,

('length', 1): 1.2582151367719674,

('length', 3): 1.164040684899018,

('length', 5): 1.1107969135114395,

('length', 7): 1.0788091491246363,

('length', 9): 0.9649699176225501,

('width', 1): 1.173235330629889,

('width', 3): 0.776724402613776,

('width', 5): 0.8581184488064216,

('width', 7): 0.7920962270887307,

('width', 9): 0.7818084447558675,

('height', 1): 1.835270961051065,

('height', 3): 1.4522475457196613,

('height', 5): 1.3712276576274274,

('height', 7): 1.2536105424726978,

('height', 9): 1.1799262400433599,

('curb-weight', 1): 0.8977925627200231,

('curb-weight', 3): 0.7810203611189004,

('curb-weight', 5): 0.7526797743700095,

('curb-weight', 7): 0.7273112573379618,

('curb-weight', 9): 0.6962953604831444,

('engine-size', 1): 0.711130777393697,

('engine-size', 3): 0.6670315366668025,

('engine-size', 5): 0.6066522674323407,

('engine-size', 7): 0.5846523661450151,

('engine-size', 9): 0.5470224273794155,

('compression-rate', 1): 0.9995557239010212,

('compression-rate', 3): 1.0014666665882759,

('compression-rate', 5): 0.9980929742948769,

('compression-rate', 7): 0.994312348888388,

('compression-rate', 9): 0.9657803897563202,

('city-mpg', 1): 0.672247401307514,

('city-mpg', 3): 0.6692599843503406,

('city-mpg', 5): 0.6071818370617673,

('city-mpg', 7): 0.5947058619062482,

('city-mpg', 9): 0.6184289881119851,

('highway-mpg', 1): 0.65226957297654,

('highway-mpg', 3): 0.5514192730892143,

('highway-mpg', 5): 0.5904065996733864,

('highway-mpg', 7): 0.5316220529521046,

('highway-mpg', 9): 0.5045969744641035,

('horsepower', 1): 0.7424499390187735,

('horsepower', 3): 0.751441782151203,

('horsepower', 5): 0.6212450466337898,

('horsepower', 7): 0.5678990997984015,

('horsepower', 9): 0.51029924508396,

('peak-rpm', 1): 1.2547163045227205,

('peak-rpm', 3): 1.1322701001836366,

('peak-rpm', 5): 1.1696138374863996,

('peak-rpm', 7): 1.1987345300306547,

('peak-rpm', 9): 1.1998145119829764}

We can observe that there are multiple univariate models with low rmse. Nevertheles, we can find out the one with smallest rmse.

# find the feature and k with minimum rmse

minval = min(lowest_rmse.values())

res = [k for k, v in lowest_rmse.items() if v == minval]

print("Model with lowest rmse is based on feature:{} with k={}".format(res[0][0], res[0][1]))

Model with lowest rmse is based on feature:highway-mpg with k=9

Multivariate Model

Let’s modify the function we wrote to work with multiple columns.

# function to knn_model training and validation

# modified for multivariate modeling

def knn_train_test(train_name, target_name, data, k=5):

# make a copy of the dataset

df = data.copy()

# number of observations for split

obs = int(df.shape[0] / 2)

if len(train_name) <= 1:

return "Please provide a list of features"

# split the data into train and test

train_df = df.iloc[:obs]

test_df = df.iloc[obs:]

# instantiate and fit the model

knn = KNeighborsRegressor(n_neighbors=k)

knn.fit(train_df[train_name], train_df[target_name])

# make predictions and evaluate

preds = knn.predict(test_df[train_name])

rmse = mean_squared_error(test_df[target_name], preds) ** (1/2)

return rmse

To test our new function, we will choose the best 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 features sequentially from the univariate model exploration and train using the default value of k=5.

# features ordered by performance from univariate modeling

features = ['highway-mpg', 'horsepower', 'engine-size',

'city-mpg', 'curb-weight']

# starting feature set

cols = features[:1]

# iterate and add each feature to the next model

for col in features:

# add the next feature

cols.append(col)

# train the model

res = knn_train_test(cols, 'price', cars)

# print the rmse

print("The model with {} features has rmse:{}".format(cols,res))

The model with ['highway-mpg', 'highway-mpg'] features has rmse:0.5904065996733864

The model with ['highway-mpg', 'highway-mpg', 'horsepower'] features has rmse:0.6622571328368921

The model with ['highway-mpg', 'highway-mpg', 'horsepower', 'engine-size'] features has rmse:0.5902520717106036

The model with ['highway-mpg', 'highway-mpg', 'horsepower', 'engine-size', 'city-mpg'] features has rmse:0.5614448491361091

The model with ['highway-mpg', 'highway-mpg', 'horsepower', 'engine-size', 'city-mpg', 'curb-weight'] features has rmse:0.7406898108805515

We can observe from the results above that the model with 5 features has the best rmse.

Hyperparameter Tuning

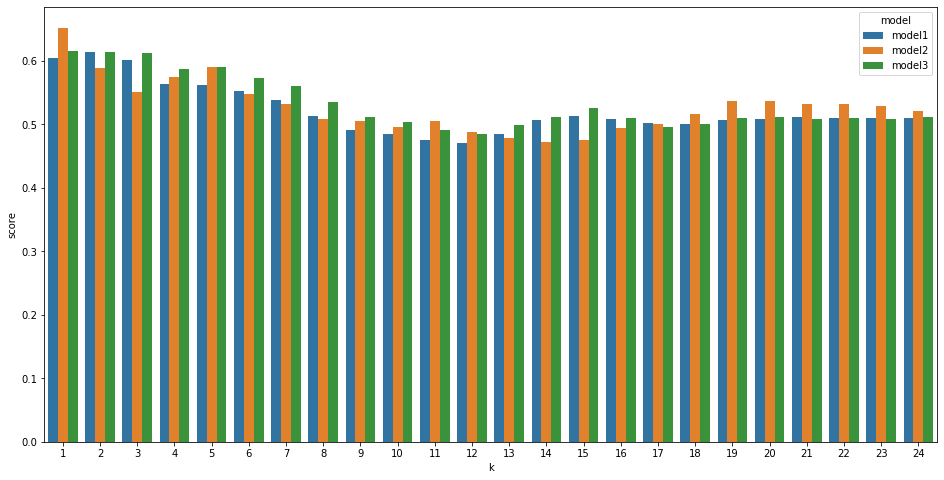

Last, but not least, we will perform hyperparameter tuning in order to find the best k parameter for our top 3 models from the last section. We will visualize the hyperparameter tuning for each model in order to find out the optimal set.

# list of features of top models

model1 = ['highway-mpg', 'highway-mpg', 'horsepower', 'engine-size', 'city-mpg']

model2 = ['highway-mpg', 'highway-mpg']

model3 = ['highway-mpg', 'highway-mpg', 'horsepower', 'engine-size']

# dataframe to hold the results

results = []

# iterate through various k values

for k in range(1,25):

# calculate the rmse for models

res1 = knn_train_test(model1, 'price', cars, k=k)

res2 = knn_train_test(model2, 'price', cars, k=k)

res3 = knn_train_test(model3, 'price', cars, k=k)

# save the results to the df

results.append(['model1', k, res1])

results.append(['model2', k, res2])

results.append(['model3', k, res3])

# convert list of list to df

df = pd.DataFrame(results, columns=['model', 'k', 'score'])

df.dtypes

model object

k int64

score float64

dtype: object

# visualize the results

import seaborn as sns

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(16,8))

sns.barplot(x='k', y='score', hue='model', data=df)

plt.show()

The bar chart displays the rmse for each model across k values. We can observe that model 2 has lower rmse consistently but all three models have lower rmse around k=12-14. We can also see that past k values of 15 the rmse started going up again and this indicates that our models started to overfit in for those k values. Nevertheless, k values around 12-14 seem like a good choice for the k parameter.

Summary & Ideas

In this project we build a knn classifier and trained both univariate and multivariate models with varying k values. Some ideas on improving our function are implementing k-fold cross validations since currently we are using half of the data to train and the other half for testing, we could improve the performance and accuracy of the model by implementing k-fold cross validation and choose the k value just as we did with k value for knn.

That’s it for this project. Feel free to leave your feedback and comments here below.

For a complete jupyter notebook file please refer to the github page of the project.

Leave a comment